ingrédients pour

un univers

fait maison

Summer of 2016 I built a couple of simple 14” x 18” mobile testing platforms, intending, (thanks to the generous support of the MAI’s mentorship program) to work with a coder and explore basic robot navigation, wireless data communication, and more robust electronic assembly and signal isolation strategies.

Summer of 2016 I built a couple of simple 14” x 18” mobile testing platforms, intending, (thanks to the generous support of the MAI’s mentorship program) to work with a coder and explore basic robot navigation, wireless data communication, and more robust electronic assembly and signal isolation strategies.

But… as the summer ended and my little motorized wood-and-plexi platforms roamed through my studio, happily avoiding walls, scattered junk and confused chihuahuas, I was disappointed to find that I’d simply replicated, on a very small scale, the usual forms of production and consumption I’d intended to criticize as an artist.

I’d been drawn to robot-building because we react emotionally to their presence. Whether heroic or neurotic, they hold a special place in our contemporary imaginary, in the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves. I thought I could upend these narratives, or counter them with a digitally-mediated maximalist materiality. But, as I finished the small prototypes, I realized I upended nothing.

Acquiring the technical know-how to build 3 working robotic platforms “properly”, “predictably”, led me to reject this as a valid aim for my art practice.

We are already primed with set reactions and expectations when confronted with an electronic/digital object. It may be a mysterious black box whose inner workings we don’t understand, but it is also very familiar, to the point of being considered necessary by many. It is already a consumer product in our homes, it’s managing shopping lists and heating, it is already a wealthy tech-savvy child’s toy, or a classroom educational kit. Its identity is that of a gadget in a world of gadgets already promising indulgence, or novelty, or some nebulous safer/happier future. The only reactions were the scripted ones: Does it work all the time? How do I play with it? Can my dog/child safely play with it? How much did it cost? How many will you build? Where can I get a kit?

Unless my project consisted of an ironic manipulation of this very script, I had to find another approach.

It also crystallized the notion for me that it is not function, but dysfunction where my preoccupations lie.

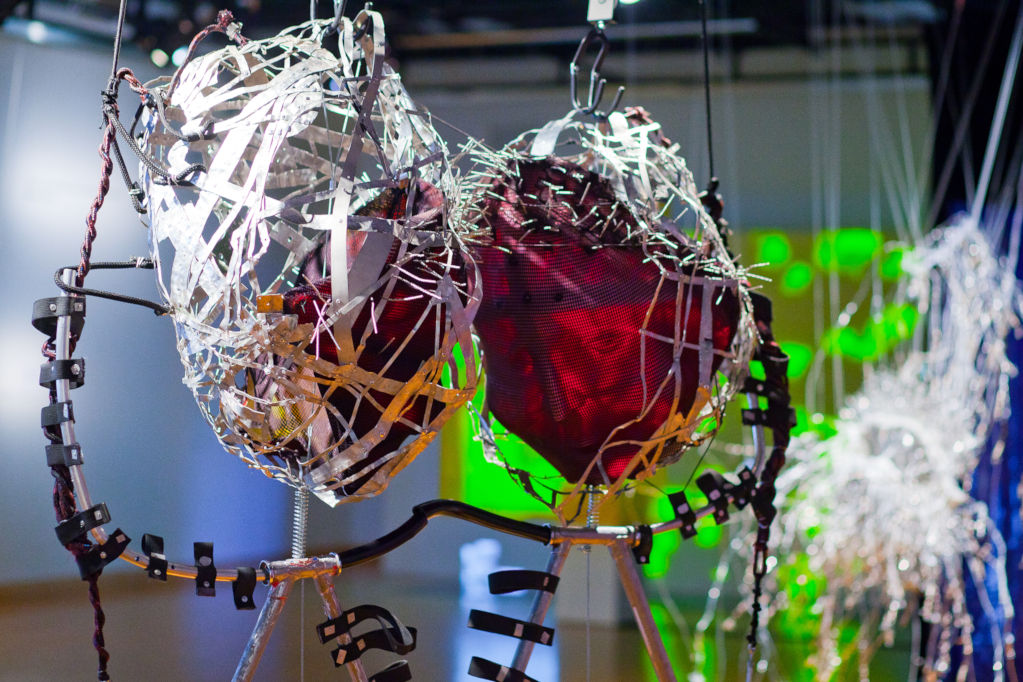

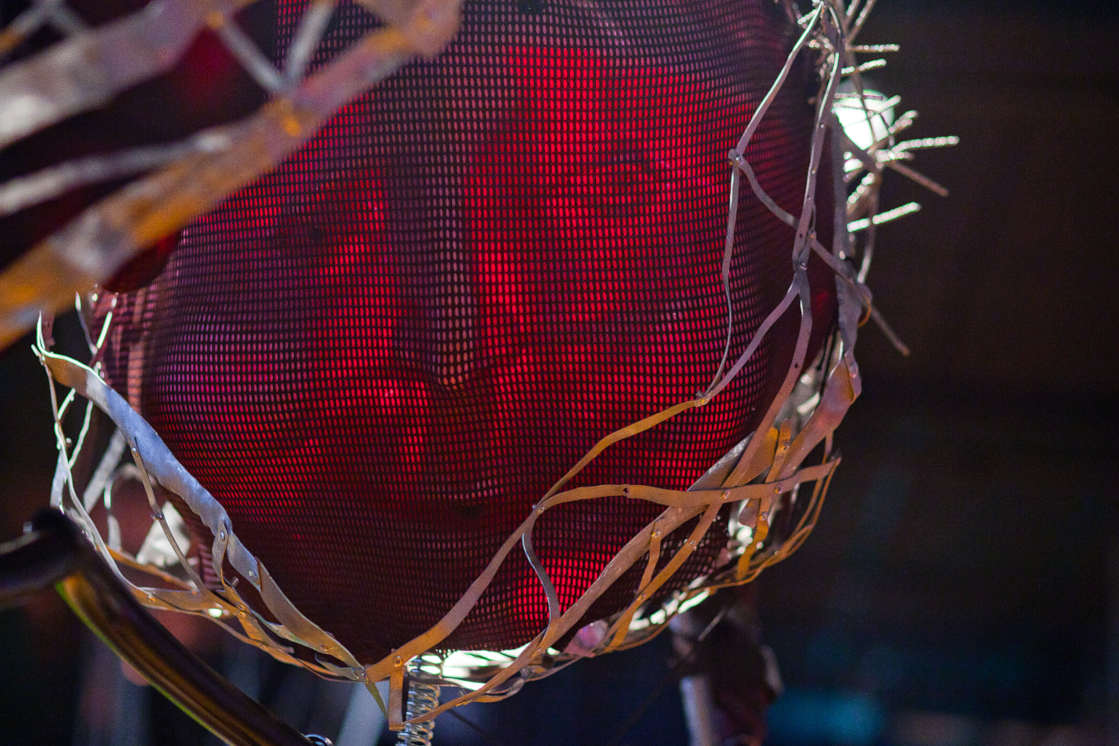

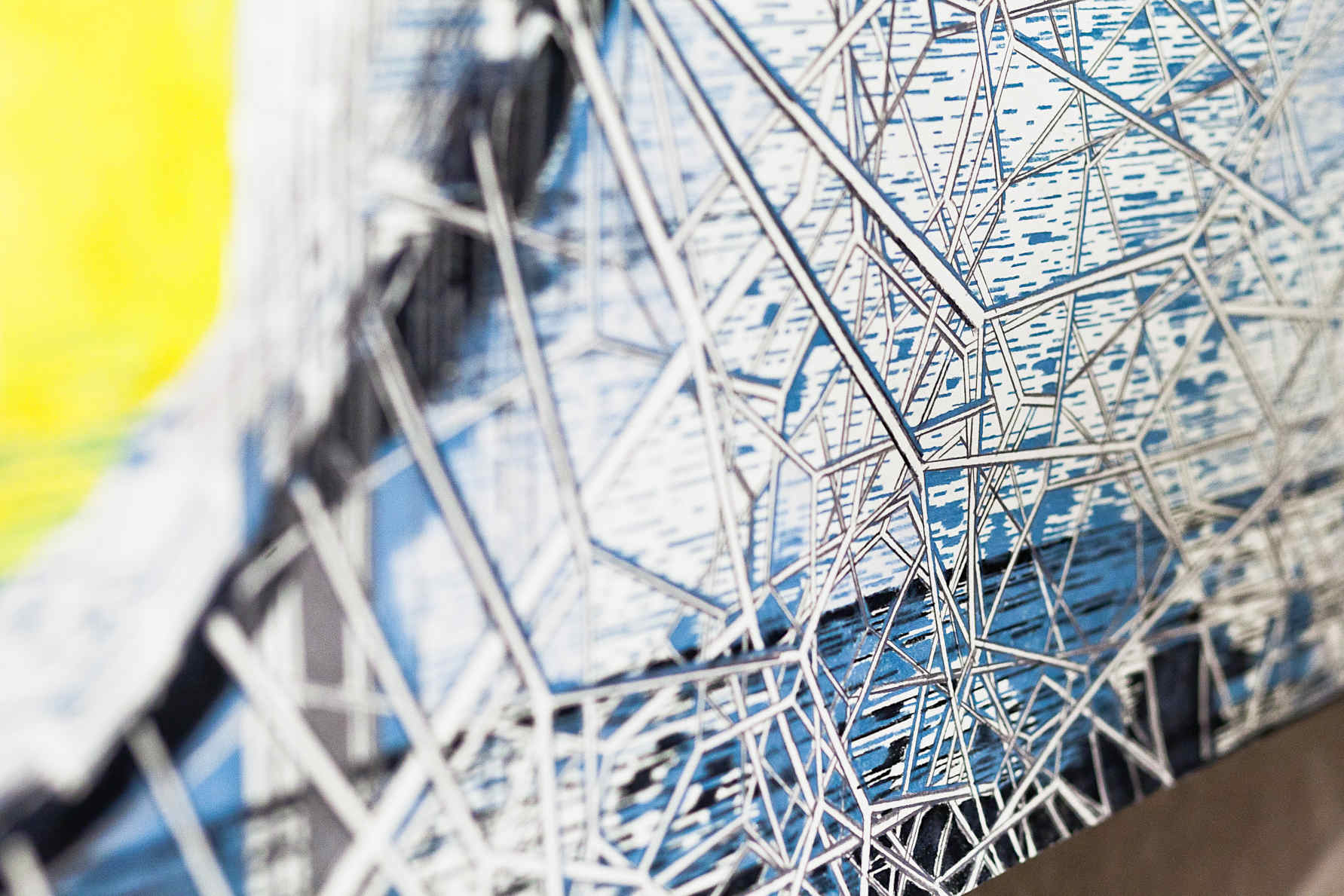

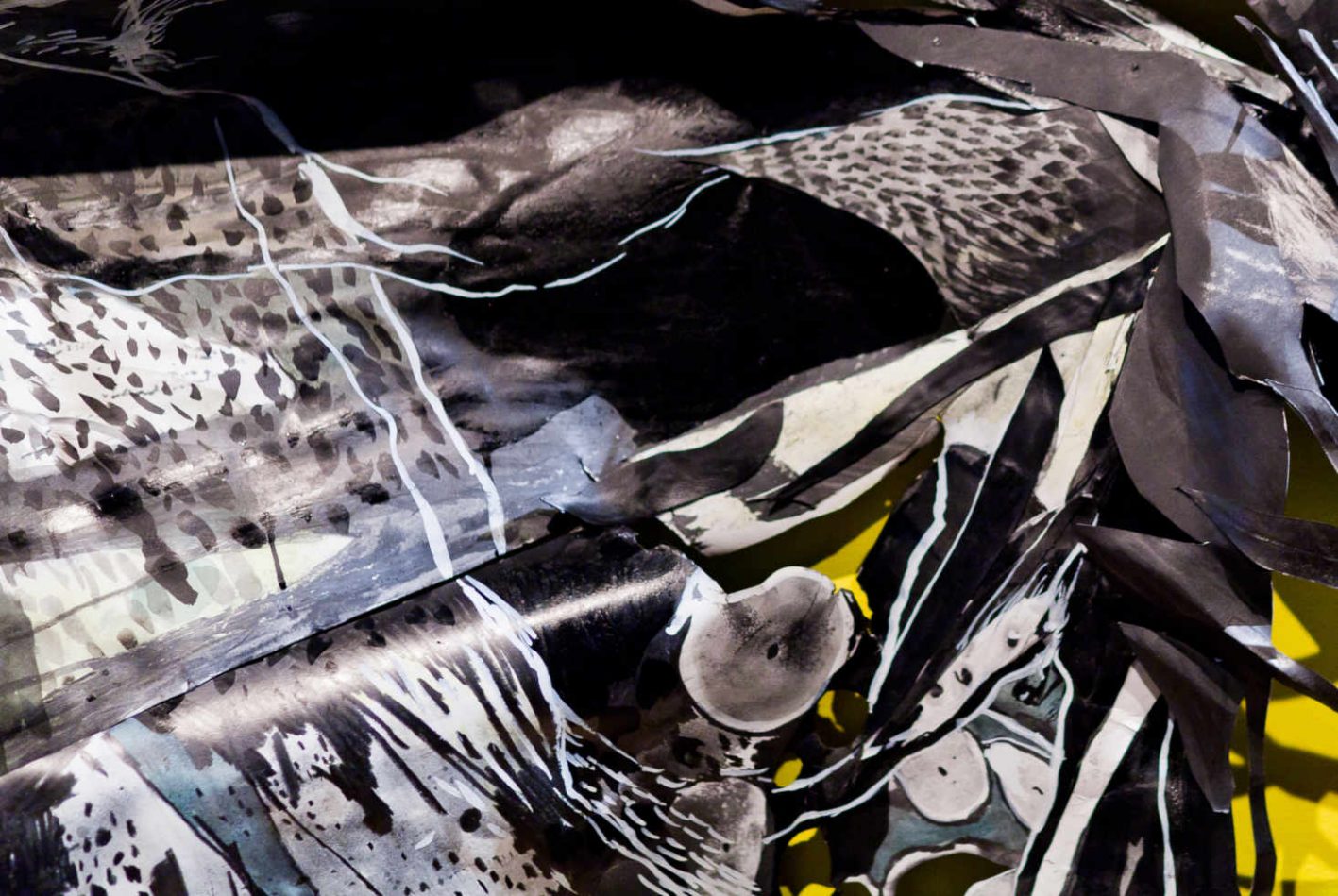

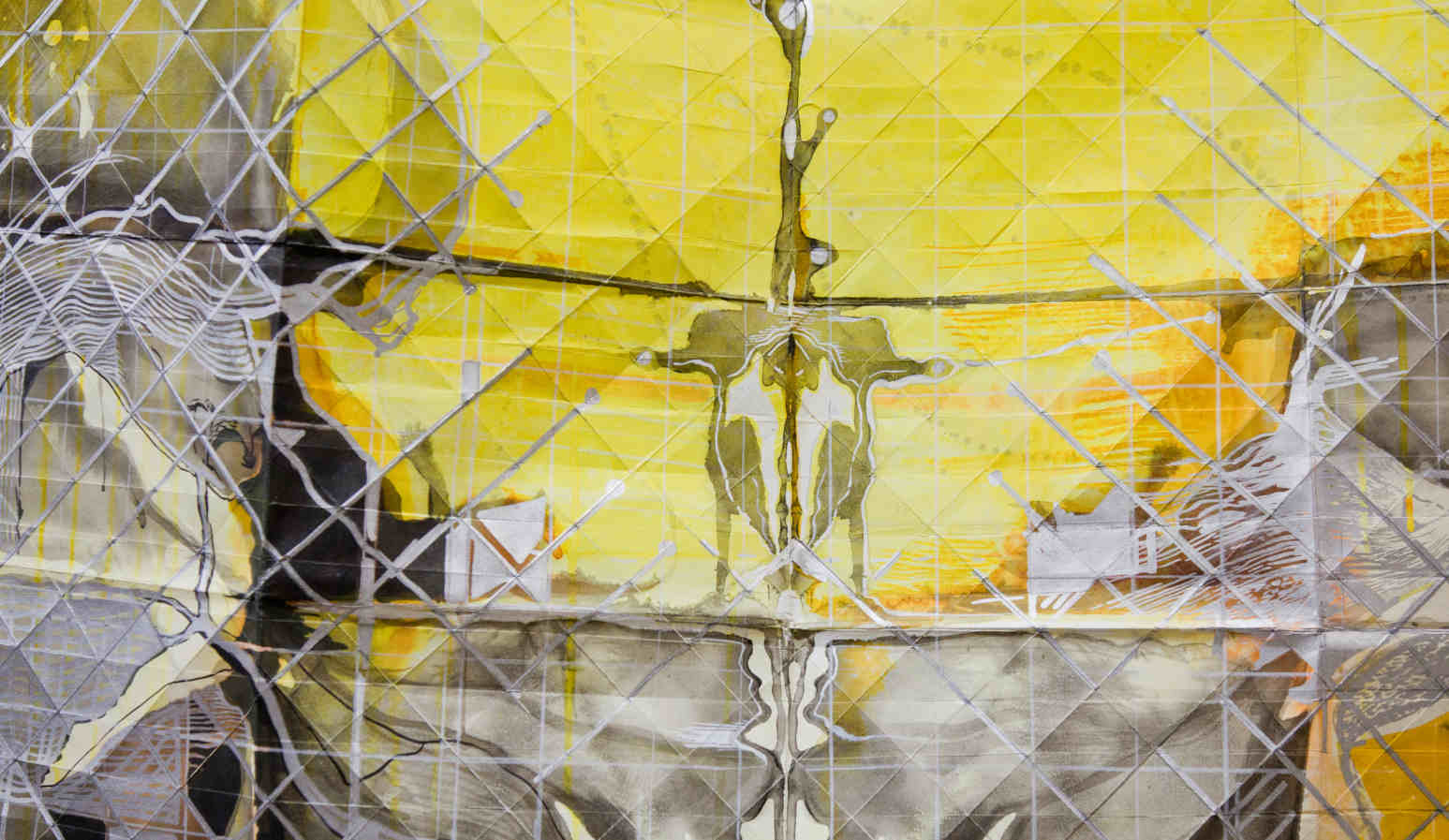

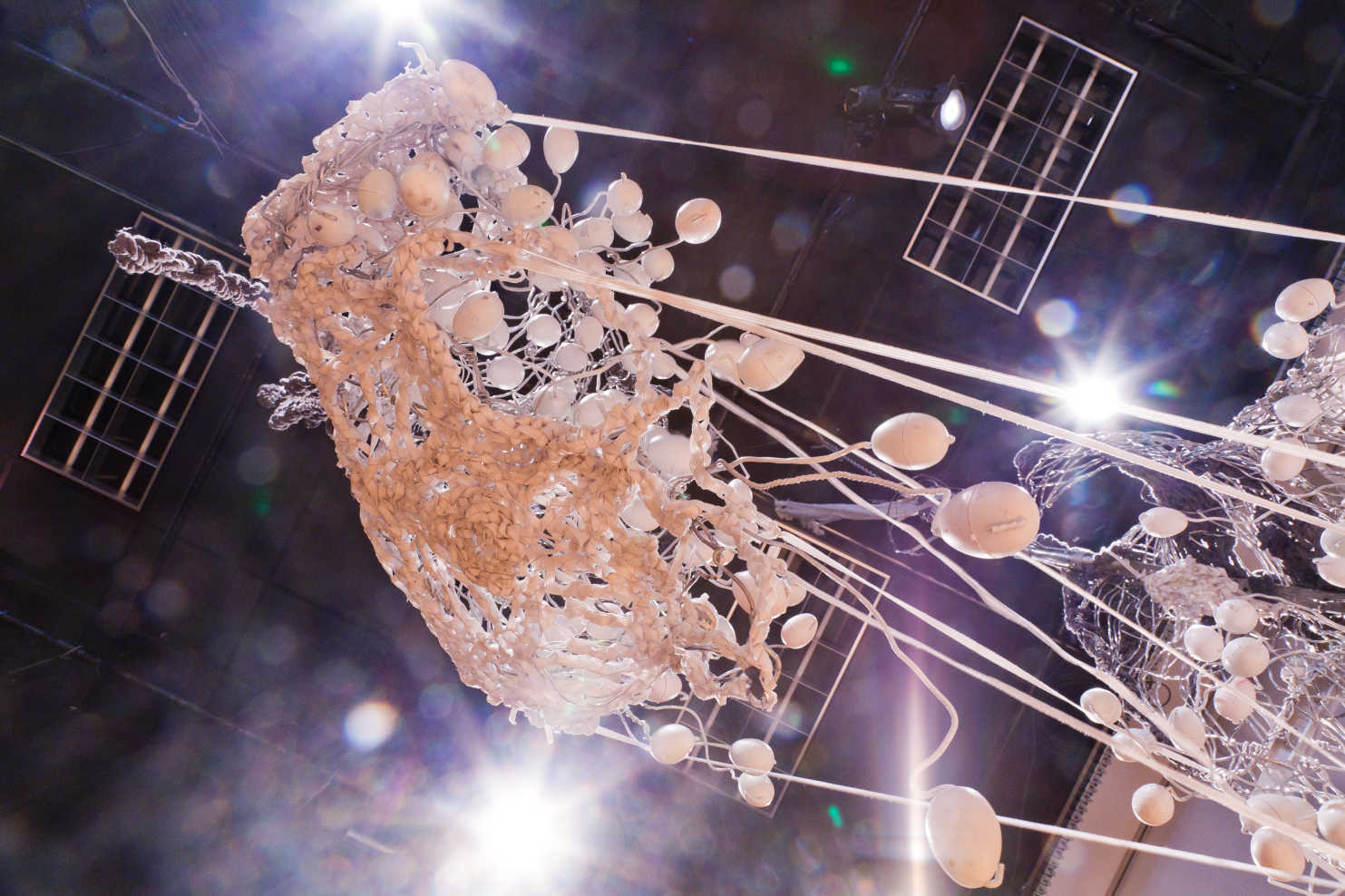

I rejected textual narratives and smart, autonomous functions. I rejected slick, expensive materials or processes, and favoured manipulations of scale, tactility, and materiality. I experimented with random or impossible navigation, with microphones, simple circuits and surface transducers; with cast-off materials woven, bolted, riveted, dyed, sewn, crocheted, programmed and drawn into aesthetically cohesive, large-scale suspended structures.

I rejected textual narratives and smart, autonomous functions. I rejected slick, expensive materials or processes, and favoured manipulations of scale, tactility, and materiality. I experimented with random or impossible navigation, with microphones, simple circuits and surface transducers; with cast-off materials woven, bolted, riveted, dyed, sewn, crocheted, programmed and drawn into aesthetically cohesive, large-scale suspended structures.

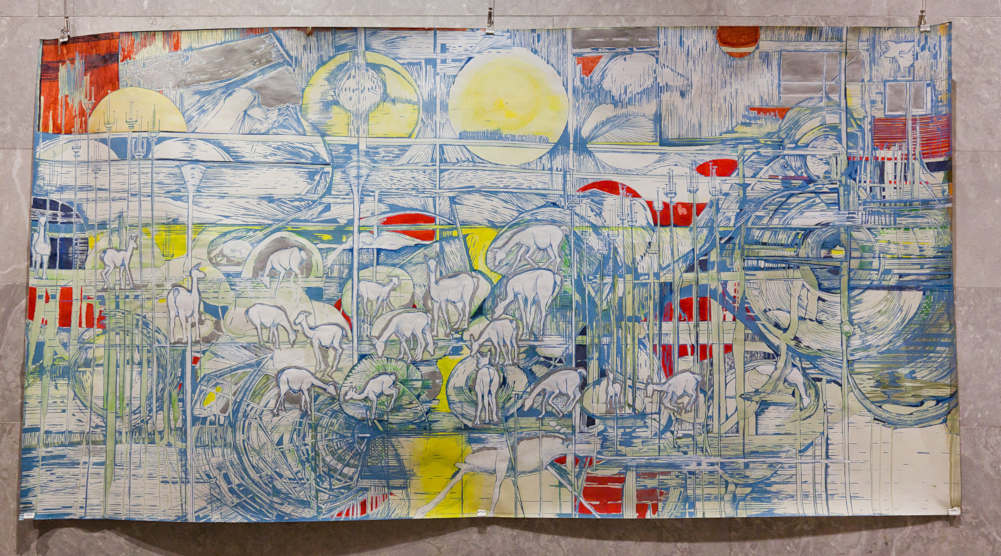

The resulting cannibalistic breakdown, and re-agglomerations of rope, leather, belt straps, metal, empty candy containers filled with metal shards, eventually became 8 sculptures and a series of approximately 30 drawings.

The works were generated through loose sets of rules. For example, I did not allow myself to buy new materials for the main structures of the sculptures, from bicycle parts, to bags of leather, or underground cable lifted from an abandoned building, it all had to be found, donated, or recycled from past work (There were still purchased materials of course: nuts, bolts, rivets, dye, ink, fabric, pencils, electronic supplies, motors etc.).

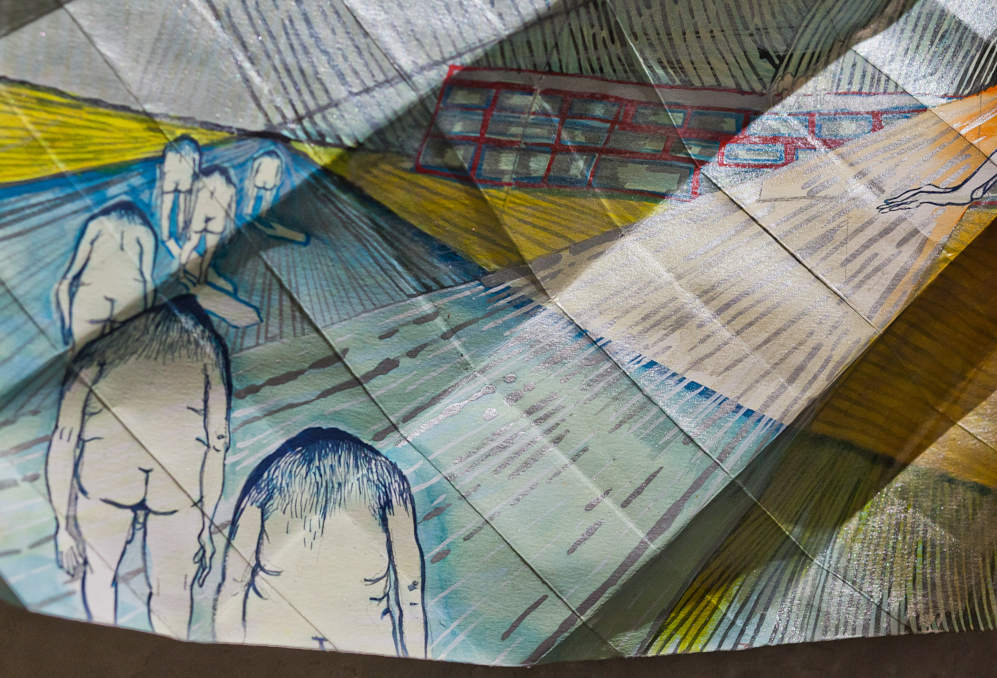

The drawings’ rules were slightly more arbitrary: “build a jig, make precise lines every 1/4” along a horizontal axis till the pencil is worn to a stub, rotate, re-align, repeat, generate a cohesive composition.” Or: “Fold a sheet of paper the size of a table till it fits in your pocket, clamp in a vice, dye with pigment, allow to dry, unfold, re-fold, dye, allow to dry, unfold, create a drawing in silver ink, re-fold, soak in water, clamp, let dry.” Not all the experiments were successful, as in the case of the drawings into which I saturated soft graphite till they conducted electricity (though conductive, they were unreliable as electrodes, and could not be incorporated into circuitry even as random noise generators, remaining aesthetic objects).

My explorations of aesthetic sensuousness and beauty were not meant as a surface effect, but as inherent structural elements of the non-anthropomorphic ecologies I was attempting to build.

I presented the works as part of an exhibition at the Maison de la culture de Parc Extension in the Fall of 2018.

For a full month I had the uncanny experience of being able to watch people watch my work. This included daily school visits and group tours. As a visual artist usually locked alone in her studio, it made me wonder about the possibilities of collaboration, of how to delight and puzzle viewers. It led me to a re-evaluation of criticality, how to get them (and myself) to move, at least a little, beyond the expectations (Yeah, but does it work? How do I play with it? What is it supposed to do?) and limitations of both digital creation and techno-consumption. In the end, I realized that to build a home-made universe, one should start by making various prototypes of her own expectations, and then trash them, or rather, recycle them, into some less superficially ambitious, but more open, vessels.